If you’re at work when you have an amygdala hijack, you can’t focus on what your job demands-you can only think about what’s troubling you. The hijack captures our attention, beaming it in on the threat at hand. We can’t innovate or be flexible during a hijack. If the amygdala detects a threat, in an instant it can take over the rest of the brain-particularly the prefrontal cortex-and we have what’s called an amygdala hijack.ĭuring a hijack, we can’t learn, and we rely on over-learned habits, ways we’ve behaved time and time again. In the brain’s blueprint the amygdala holds a privileged position. Our brain was designed as a tool for survival. “The amygdala is the brain’s radar for threat. In my book, The Brain and Emotional Intelligence, I explained:

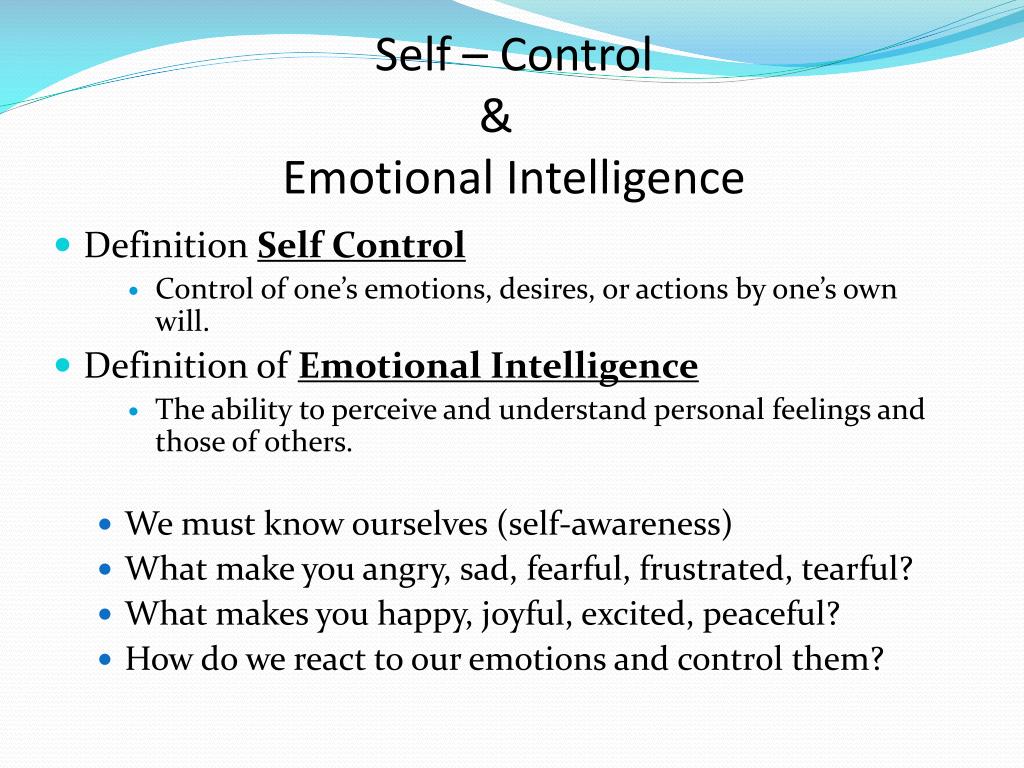

To understand the importance of emotional self-control, it helps to know what’s going on in our brain when we’re not in control. With emotional self-control, you can manage destabilizing emotions, staying calm and clear-headed. It’s one thing to do it in a heartfelt conversation with a good friend, and entirely another to release your anger or frustration at work. But we also need to allow ourselves the space and time to process difficult emotions, but context matters. We need our positive feelings-that’s what makes life rich. Notice that I said “manage,” which is different from suppressing emotions. What is Emotional Self-Control?Įmotional self-control is the ability to manage disturbing emotions and remain effective, even in stressful situations. They each lack emotional self-control, one of twelve core competencies in our model of emotional and social intelligence. In different industries, on different continents, these three leaders have this in common: their inability to manage distressing emotions hurts their effectiveness at work. Avery’s intense anxiety about upcoming funding cuts leaks out as overly critical interactions with staff members.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)